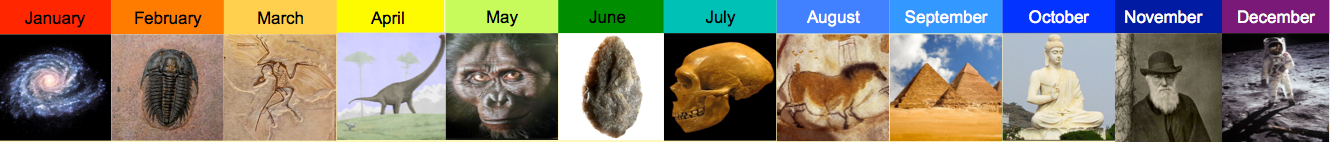

“We are upside-down bugs” is not as catchy a song lyric as “We are stardust.” But the story may be just as interesting.

The proto-evolutionist anatomist Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844) proposed long ago that all animals – insects to vertebrates — share a “unity of composition.” He was opposed by his sometime friend and sometime rival, anti-evolutionist anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), who argued that the animal world is organized in four great “embranchements,” with nothing in common in their body plans. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire noted that insects have their nervous systems running ventrally (through their bellies) and their digestive systems dorsally (through their backs), the opposite of vertebrates. So he proposed the daring hypothesis that, from head to tail, vertebrates and insects have the same body plan, but belly to back they are flipped around.

Remarkably enough, a modernized version of this hypothesis has been vindicated by developmental genetics. Vertebrates have a series of genes, the Hox genes, that control development. They are laid out in order, with the genes switching on the development of the head followed by genes for the upper body, etc. It turns out that much the same genes in the same order control development in insects (not exactly the same, but clearly related), even though the actual structure of insect bodies is very different. On the other hand, the gene that turns on ventral development in the fruit fly Drosophila is related to the gene that turns on dorsal development in the toad Xenopus, while the gene that turns on dorsal development in Drosophila is related to the gene that controls ventral development in Xenopus.

The hypothesis that seems to account for this is that back in the day –- before the Cambrian explosion – there was a small wormy bilaterally symmetrical organism, ancestor to almost all animals (except sponges and jellyfish). Some of the descendants of that primordial animal gave rise to protostomes (where the first opening in the embryo becomes a mouth) including arthropods (spiders, insects, etc.), molluscs (including clams, crustaceans, octopuses), and annelids (earthworms).

But somewhere along the pathway leading to the deuterostomes (where the first opening in the embryo becomes the anus, the second becomes the mouth), including the chordates, the vertebrates, and us, another set of descendants started swimming upside down. And the rest is (pre)history: this initial minor quirk of evolutionary history was well-entrenched by the Ordovician 480 Million years ago.

Pingback: We Are MacApes | Logarithmic History