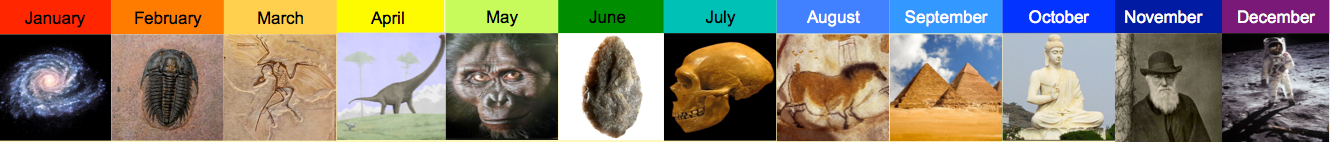

2.3-2.18 billion years ago

A few days ago, I picked up a five gallon bucket that I had left at the cafe down the street, which they nicely filled up with coffee grounds. These went into my compost heap, where they’ll supply the nitrogen that the leaf mulch in the heap is short of. I’ve developed a kind of pre-capitalist exchange relation with the cafe; summers I bring them some flowers from my garden.

It took me years to get the formula right. For a long time, I just let chopped up leaves sit in a pile in a corner of the yard. Nothing much happened. Eventually I wised up and did some research: proper composting requires the right balance of carbon and nitrogen. The nitrogen and some of the carbon go into building organic molecules. Most of the carbon, though, combines with oxygen to make carbon dioxide, releasing energy in the process for the bacteria that make the compost. The amount of energy is appreciable: on a mild winter day, with air temperature just above freezing, the inside of my compost heap was the temperature of a lukewarm bath.

But composting goes back way longer than my compost heap, and way longer than Homo sapiens has been around. In fact, composting may have gotten its start more than 2 billion years ago. Here’s the story:

Back when I was in college, a guy I knew was taking a course in organic chemistry. He despaired of mastering the material in time for the next exam. Another student who’d already taken the course advised him, “Just remember, electrons go where they ain’t. Everything else is details” This is a pretty good starting point for thinking about how life and Earth have coevolved. Carbon, sitting in the middle of the periodic table, with four electrons to share, and four empty slots available for other atoms’ electrons, is exceptionally versatile. It can form super-oxidized carbon dioxide, CO2, where carbon’s extra electrons fill in oxygen’s empty slots. Or it can form super-reduced methane, CH4, where carbon’s empty slots are filled by hydrogen’s extra electrons. Or it can form carbohydrates, basic formula CH2O, neither super-oxidized nor super-reduced, where the oxygen atom gives the carbon atom some extra empty slots and the hydrogen atoms give the carbon atom some extra electrons.

Chemically, life is pretty much about reducing and oxidizing carbon compounds. Nowadays, this means, on the one hand, photosynthesis – using the sun’s energy to go from carbon dioxide to carbohydrates – and, on the other hand, aerobic respiration – running the same reaction in reverse to release energy. But this modern arrangement took eons to develop. It depended on geochemistry, specifically on the evolution of what has been called a planetary fuel cell, with an oxidizing atmosphere and ocean physically separated from buried reduced minerals. Given a breach in this separation, the oxygen and the reduced minerals will react and release energy. In future posts we’ll see how such short-circuits in the planetary fuel cell, a result of major lava flows, are probably the cause of most major mass extinctions.

The development of the planetary fuel cell was erratic. One puzzling episode is the Lomagundi Event, where oxygen levels went up 2.2 billion years ago and then back down 2.08 billion years ago. One theory is that the Event began with photosynthetic cyanobacteria pumping oxygen into the atmosphere. When these bacteria died, they just piled up, leaving a growing accumulation of organic matter in the world’s oceans. According to this theory, the end of the Event happened when other bacteria discovered they could oxidize the accumulated organic matter, and used up a good part of the atmosphere’s oxygen. In other words, the end of the Lomagundi Event marks the invention of composting.

The return to higher oxygen levels in the atmosphere would take some time, and deposition of reduced sediments.

Pingback: The worst of times | Logarithmic History

Pingback: Compost | Logarithmic History