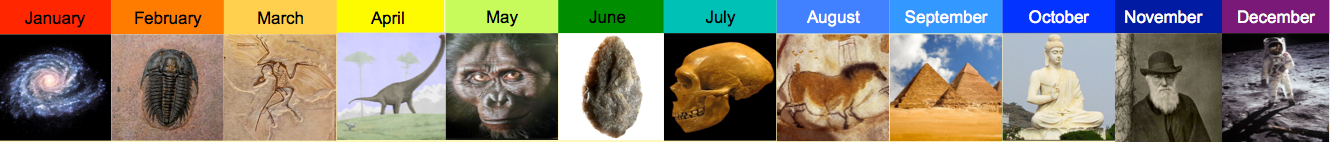

930 – 881 thousand years ago

On June 3 on Logarithmic History, our ancestors had gotten as far as steak tartare. Now it’s time for an Eisenhower steak (cooked directly on the coals; see below).

What really distinguishes humans from other animals? We’ve covered some of the answers already, and will cover more in posts to come. But certainly one of the great human distinctions is that we alone use fire. Fire is recognized as something special not just by scientists, but in the many myths about how humans acquired fire. (It ain’t just Prometheus.) Claude Lévi-Strauss got a whole book out of analyzing South American Indian myths of how the distinction between raw and cooked separates nature from culture. (I admit this is where I get bogged down on Lévi-Strauss.)

Until recently the story about fire was that it came late, toward the latter days of Homo erectus. But Richard Wrangham, a primatologist at Harvard, turned this around with his book Catching Fire (which is not the same as this book), arguing that the taming of fire goes back much earlier, to the origin of Homo erectus. Wrangham argues that it was cooking in particular that set us on the road to humanity. Cooking allows human beings to extract much more of energy from foods (in addition to killing parasites). Homo erectus had smaller teeth and jaw than earlier hominins and probably a smaller gut, and it may have been fire that made this possible. Cooking is also likely to have affected social life, by focusing eating and socializing around a central place. (E O Wilson thought that home sites favored intense sociality in both social insects and humans.)

Surviving on raw food is difficult for people in a modern high-tech environment and probably impossible for people in traditional settings. Anthropologists are always looking for human universals, and almost always finding exceptions (e.g. the vast majority of societies avoid regular brother-sister marriage, but there are a few exceptions, including Roman Egypt and Zoroastrian Iran). But cooking seems to be a real, true universal. No society is known where people got by without cooking. Tasmanians, isolated from the rest of the world for 10,000 years, with the simplest technology of any people in recent history, had supposedly lost the art of making fire, but still kept fires going and still cooked.

Recent archeological finds have pushed the date for controlled use of fire back to 1 million years ago, but not all the way back to the origin of Homo erectus. This doesn’t mean Wrangham is wrong. Fire sites don’t always preserve very well: we have virtually no archeological evidence of the first Americans controlling fire, but nobody doubts they were doing it. It could be that it will be the geneticists who will settle this one. The Maillard (or browning) reaction that gives cooked meat much of its flavor generates compounds that are toxic to many mammals but not (or not so much) to us. At some point we may learn just how far back genetic adaptations to eating cooked food go.

An alternative to an early date for fire, there is the recent theory that processing food, by chopping it up and mashing it with stone tools, was the crucial early adaptation.

Whenever it is exactly that humans started cooking, the date falls in (Northern hemisphere) grilling season on Logarithmic History, so you can celebrate the taming of fire accordingly. It doesn’t have to be meat you grill. Some anthropologists think cooking veggies was even more important. I particularly recommend sliced eggplant, brushed with olive oil to keep it from sticking, and with salt, pepper, and any other spices. And grilled pineapple slices, with honey, are very good

On the other hand, Homo erectus probably appreciated a good Eisenhower steak, cooked directly on the coals. (Yes, this actually works pretty well.)

Named for the 34th president of the United States, who liked to cook his steaks directly on the coals, this preparation will create a crunchy, charred exterior with rosy, medium-rare meat inside.

Lump hardwood coals work better than briquettes for this recipe because they burn hotter. Be sure you use long-handled tongs. (Sorry, this method is for charcoal or wood grilling only.)

You might find an uneven exterior crust, especially when using lump charcoal, because it is irregularly shaped (unlike the uniform briquette pillows). If that happens, try to position the steak so that it is more directly on the coals and gets an even char. Clasp the steak in the tongs and rap the tongs against the edge of the grill to knock off the occasional clinging ember. If you have some ash, flick it off with a pastry brush.

Make Ahead: The steaks can be seasoned and refrigerated up to 4 hours in advance. Bring them to room temperature before they go on the fire.

INGREDIENTS

- 1 teaspoon olive oil

- Two 1 1/2-inch-thick boneless rib-eye steaks (about 28 ounces total)

- 2 teaspoons coarse sea salt

- 2 teaspoons freshly cracked black pepper

DIRECTIONS

Prepare the grill for direct heat. Light the charcoal; when the coals are just covered in gray ash, distribute them evenly over the cooking area. For a hot fire (450 to 500 degrees), you should be able to hold your hand about 6 inches above the coals for 2 or 3 seconds. Have a spray water bottle at hand for taming any flames. But use it lightly; you don’t want to dampen the heat too much, and some flames here are fine.

Meanwhile, brush the oil on the both sides of the steaks, then season both sides liberally with salt and pepper.

Once the coals are ready, place the steaks directly on the coals (see headnote). Cook, uncovered, for 6 minutes on one side, then use tongs to turn them over. Cook for about 5 minutes on the second side.

Transfer the steaks to a platter to rest for 10 minutes. Serve as is, or cut them into 1/2-inch-thick slices.