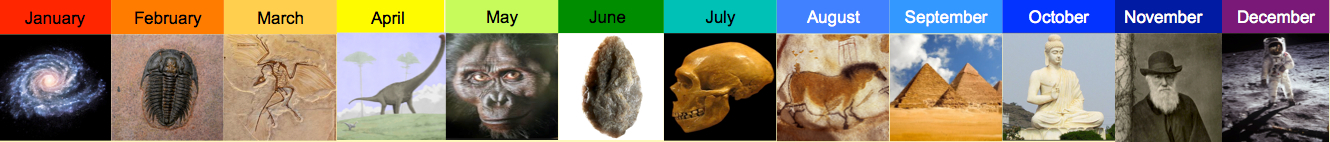

205 – 195 thousand years ago

We’re now doing history at ten thousand years a day.

Earth Abides is an early (1949) entry in the genre of post-apocalyptic science fiction, with some haunting reflections on what it takes to keep a civilization going, or just a human community. In this case the apocalypse takes the form of a lethal infectious disease that wipes out well over 99% of Earth’s human population, leaving scattered survivors to try and put things back together.

The drama is low-key. If you want to read about the remnants of civilized humanity defending themselves against zombies, or venomous man-eating walking plants, or a horde of cannibal anti-nuke zealots, you’ll have to look elsewhere. The threat to civilization in Earth Abides is more subtle. The generation born after the die-off has no understanding of what they have lost, of what the collapsing factories and powerlines and machines around them really were, or how they worked, or how to get them back up and running. The older generation, without the institutions of a complex society backing them up, can’t supply enough discipline and punishment to pass on the arts of civilization. The young will grow up as illiterate scavenger-foragers, skilled with bow and arrow, well-adapted in their own way to a rewilding Earth. Ish, the protagonist, will end his days as the Last American (a fictional counterpoint to the real-life Ishi, the last Yahi Indian).

The community is nonetheless capable of reacting decisively when their survival is threatened.

One day a newcomer enters the scene. Charlie is talkative, forceful, charismatic. The kids adore him. It looks like he might even take over as leader of the little group. But it becomes clear that there is something off about him, even sociopathic. He can turn on the charm, but when thwarted he is menacing. He always carries a gun, which he keeps hidden. He is sexually abandoned. And, in a world without antibiotics, he is infected with a slew of venereal diseases.

Something has to be done about Charlie, and the elders of the group meet to decide what. Their options are limited. Keeping him locked up is not a practical possibility for this tiny community. They could banish him. But who is to say he won’t find a gun, and come back, looking for revenge? They could execute him. But what actual harm has he done, so far? They decide to settle the matter with a vote.

Em located four pencils. Ish tore a sheet of paper into four small ballots.

…

This we do, not hastily; this we do, not in passion; this we do, without hatred. …

This is the one who killed his fellow unprovoked; this is the one who stole the child away; this is the one who spat upon the image of our God; this is the one who leagued himself with the Devil to be a witch; this is the one who corrupted our youth; this is the one who told the enemy of our secret places.

We are afraid but we do not talk of fear. … We say, “Justice”; we say, “The Law”; we say “We, the people”; we say, “The State.”

…

Ish sat with his pencil poised … He could not be sure. Yet, at the same time, he knew that The Tribe faced something real and dangerous and even dreadful, in the long run threatening its very existence. … In that final realization, he knew that he could write only the one word there, out of love and responsibility for his children and grandchildren. …

“Give me your slips,” he said.

They passed them in, and he laid them face up before him on the desk. Four times he looked, and he read: “Death … death … death … death.”

Keith Otterbein is an anthropologist who did a study of capital punishment across cultures. He expected to find that capital punishment is limited to complex societies, used to enforce social hierarchy. Instead he found that capital punishment is a universal, present in societies from the simplest to the most complex. It is an option that even the smallest, most easy-going communities – like The Tribe of Earth Abides – may find themselves resorting to. We can infer that for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors have been carrying out group-sanctioned executions of individuals deemed anti-social and a threat to group harmony and survival. This is long enough to have had evolutionary consequences. Long before we domesticated the wolf, the wild sheep and goat, the aurochs, we may have been domesticating ourselves, weeding out the wildest and most dangerous from our midst, replacing the old tyranny of the alpha male with the new tyranny of Custom and The Law.

The idea that human beings are in some ways like domesticated animals is an old one. It has recently returned to the spotlight. The extraordinary long-term experiment in artificial selection for tameness in foxes carried out by Nikolai Belyaev, Lyudmila Trut, and their coworkers in Russia has demonstrated that selection for tameness ends up selecting for a whole suite of anatomical characteristics as byproducts. Strikingly, many of the features that differentiate Homo sapiens hundreds of thousands of years ago from Homo sapiens today are also features that distinguish tame from wild foxes, and dogs from wolves.

Richard Wrangham’s recent book, The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution connects the dots, setting out one long argument that an evolutionary history of capital punishment has reduced our disposition for reactive aggression (the hot-blooded, spur-of-the-moment, volatile, antisocial kind), while leaving intact our capacity for calculated, cold-blooded, proactive killing (“not hastily, … not in passion, … without hatred”).

Perhaps this explains a very recent finding in human evolution. Apparently 200,000 years ago, we were about evenly matched with Neanderthals, sometimes replacing them, sometimes being replaced by them. By 40,000 years ago however, Neanderthals lose out decisively to modern humans. It may be that what changed in the interim to give us the edge is that we improved our ability to get along peaceably with insiders (including distant insiders we don’t know personally) without losing our ability to apply lethal aggression to outsiders.