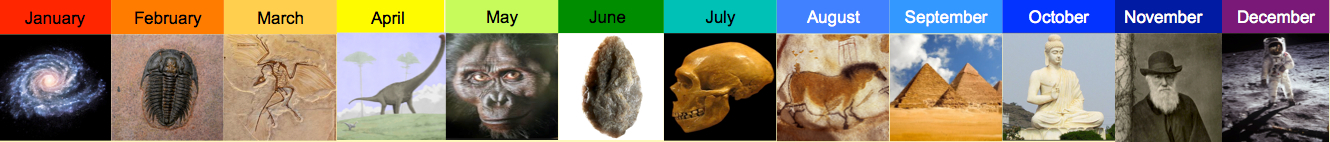

Or the Preparation of Favorite Dishes in the Struggle for Dinner.

567 – 537 million years ago

The Cambrian explosion — shells and skeletons, and all the major animal phyla of today — is one of the major events in the history of life. It’s hard to miss – Darwin was well aware of it – because for the first time you have abundant well-preserved fossils of animals with hard parts. From now on, if I miss a tweet one day or another, it’s because I didn’t get to it, not because the evidence isn’t there.

Genetic evidence seemingly clashes with the fossil evidence. A “molecular clock” based on rates of gene divergence suggests that major animal phyla had begun diverging from one another long before the Cambrian explosion. But maybe the genetic evidence is wrong, and the “molecular clock” was running faster in the past than more recently. Or maybe complex organisms evolved long before the Cambrian, but left little or no fossil evidence. Or maybe the ancestors of today’s animals really did diverge early, but didn’t get complex until the Cambrian.

And why the explosion happened when it did is unresolved. Here’s a recent review. The early Snowball Earth episodes probably contributed in some way, and the rise of oxygen in the atmosphere must have been important. Or maybe there was some dramatic biological event that triggered the explosion: the origin of eyes, and/or the beginning of predation, setting off an arms race between predators and prey that’s been going on ever since.

If this last possibility is correct, then the transition from an Edenic, predator-free Ediacaran world to the Cambrian is a form of “symmetry breaking.” There is maybe an analogy here in human social evolution to the transition from an egalitarian society to a world of inequality, of rulers and ruled (which also followed a – much milder – glacial episode).

Speaking of predation: the Logarithmic History blog is partly about commemorating great events in the past. It seems fitting to celebrate the Cambrian as the origin of seafood. If you take your time machine back to any time before the Cambrian, pickings will be slim – algae mostly, although we don’t really know what the Ediacara would have tasted like. The time-traveller’s menu gets a lot better with the Cambrian (although wood for a fire is still a problem). Nowadays you can’t hope to dine on trilobite, alas. (Check out March 13 last year for more of this sad story.) But sometime in the next few days why not have some mussels for dinner? (The recipe below has some non-Cambrian ingredients. It will be a few more days, incidentally, before the evolution of anything kosher.)

Wash and debeard:

4 to 6 pounds mussels

Place them in a large pot and add:

½ cup dry white wine

½ cup minced fresh parsley or other herbs

2 tablespoons chopped garlic

Cover the pot, place it over high heat, and cook, shaking the pot occasionally, until most of the mussels are opened, about 10 minutes. Use a slotted spoon to remove mussels to a serving bowl, then strain the cooking liquid over them. Drizzle over the mussels:

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

Juice of 1 lemon

Serve with:

Plenty of crusty bread (invented< 15,000 years ago, but who’s counting?)