17.6 – 16.7 million years ago

We are now covering history at the rate of one million years a day

The Miocene (23 – 5 million years ago) is a period of extraordinary success for our closest relatives, the apes. Overall there may have been as many as a hundred ape species during the epoch. Proconsul (actually several species) is one of the earliest. We will meet just a few of the others over the course of the Miocene, as some leave Africa for Asia, and some (we think) migrate back.

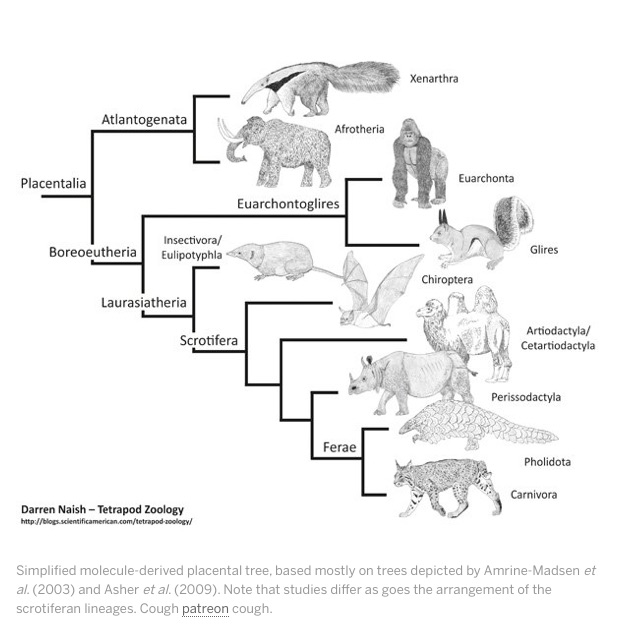

Sometimes evolution is a story of progress – not necessarily moral progress, but at least progress in the sense of more effective animals replacing less effective. For example, monkeys and apes largely replace other primates (prosimians, relatives of lemurs and lorises) over most of the world after the Eocene, with lemurs flourishing only on isolated Madagascar. This replacement is probably a story of more effective forms outcompeting less effective. And the expansion of brain size that we see among many mammalian lineages throughout the Cenozoic may be another example of progress resulting from evolutionary arms races.

But measured by the yardstick of evolutionary success, (non-human) apes — some of the brainiest animals on the planet — will turn out not to be all that effective after the Miocene. In our day, we’re down to just about four species of great ape (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans), none of them very successful. Monkeys, with smaller body sizes and more rapid reproductive rates, are doing better. For that matter, the closest living relatives of primates (apart from colugos and tree shrews) are rodents, who are doing better still, mostly by reproducing faster than predators can eat them.

So big brains aren’t quite the ticket to evolutionary success that, say, flight has been for birds. One issue for apes may be that with primate rules for brain growth – double the brain size means double the neurons means double the energy cost – a large-bodied, large brained primate (i.e. an ape) is going to face a serious challenge finding enough food to keep its brain running. It’s not until a later evolutionary period that one lineage of apes really overcomes this problem, with a combination of better physical technology (stone tools, fire) and better social technology (enlisting others to provision mothers and their dependent offspring).