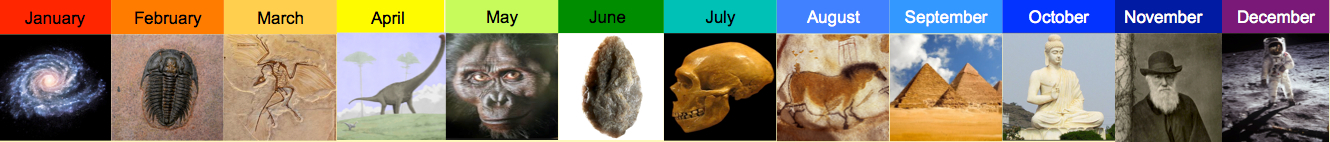

Only in the last half century or so, with the discovery of the Big Bang, has it been possible to do something like Logarithmic History. But human beings have been speculating for far longer than that on the origins of the universe, and we’ll have plenty of occasions here to pay tribute to earlier prescientific cosmologies. (The early chapters of the book of Genesis are probably most familiar to Western readers, but there are lots of others.)

Strikingly, it may be possible to reconstruct a very early interconnected set of myths concerning the world’s origin, which date back to long before the invention of writing (or farming, for that matter). This is the argument of Michael Witzel and some of his associates, set forth at length in Witzel’s ambitious recent book, The Origins of the World’s Mythologies. Witzel is an expert on the Vedas (Hindu sacred texts)* who has grown interested in wider comparisons. He argues that there are striking parallels in myths told in traditional societies across a wide expanse of the Earth. These parallels are not the product ancient archetypes welling out of the collective unconscious, but are survivals of a coherent narrative of the origins and destiny of the universe, the gods, and humans, which was told tens of thousands of years ago. This mythological narrative includes the following:

In the beginning: primordial waters / darkness / chaos / ‘nonbeing’

A primordial egg / giant

A primordial hill / island / floating earth

Father Sky and Mother Earth and their children, for four generations, defining Four Ages of creation

The Sky is raised up and severed from the Earth

The Sky and his daughter commit incest, and the hidden sun’s light is revealed

The current generation of gods defeat or kill their predecessors.

A dragon is slain by a culture hero

The Sun becomes the father of humans (later on, of chieftains), and establishes their rituals

The first humans, whose evil deeds lead to the origin of death and the great Flood

A generation of heroes and the bringing of fire / food / culture by a culture hero

The spread of humans / emergence of local nobility: local history begins

In the future: final destruction of humans, the world, the gods

A new heaven and a new earth / eternal bliss

Some elements of the myth seem to have an astronomical significance. The revelation of the sun seems to be especially associated with the winter solstice, and the slaying of a dragon, bringing rain, with the summer solstice. The Greek version of the Four Ages (and its Near Eastern antecedents) is clearly related to the movements of stars and planets.

Witzel labels the resulting mythic narrative “Laurasian mythology,” because its major elements are found mostly in Eurasia, the Pacific, and the New World. It contrasts with a Gondwanan mythology found Africa, New Guinea and Australia. (These two mythologies happen, by chance, to correspond roughly to the ancient supercontinents of Laurasia and Gondwana.) Laurasian and Gondwanan mythology overlap to some extent. Stories of a great Flood sent to punish unruly or sinful mankind, leaving only scattered mountaintop survivors to repopulate the world, are found in both.**

Witzel proposes that Laurasian mythology dates all the way back to an Out Of Africa expansion 40 thousand years ago. I have chosen fairly arbitrarily to introduce it instead at a later date. But it can’t date any later than the main settlement of the Americas by the ancestors of Amerindians.

* Witzel’s work on the Vedas has led to his being dogged by a lot of Hindu nationalists who are outraged that he thinks Indo-European languages came from outside India, an occupational hazard for the Indo-Europeanist scholar.

** When I did fieldwork several decades ago among the Ache Indians in Paraguay, they were curious about the way the story of Noah seemed to fit with their own flood story.