156 – 149 million years ago

The first Archaeopteryx discovered, found in 1861, is the most famous fossil ever (barring maybe some close human relations). It came at the right time, providing dramatic evidence for the theory of evolution.

There may be psychological reasons why Archaeopteryx had the impact it did. Here’s my argument anyway:

According to Jorge Luis Borges, the following is a classification of animals found in a Chinese encyclopedia, the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge.

- Those that belong to the Emperor

- Embalmed ones

- Those that are trained

- Suckling pigs

- Mermaids (or Sirens)

- Fabulous ones

- Stray dogs

- Those that are included in this classification

- Those that tremble as if they were mad

- Innumerable ones

- Those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush

- Et cetera

- Those that have just broken a flower vase

- Those that, at a distance, resemble flies

Although some scholars have taken this list seriously (Hi, Michel Foucault!), there’s no evidence that this is anything but a Borgesian joke. Anthropologists have actually spent a lot of time investigating the principles underlying native categorizations of living things, and found they are not nearly as off-the-wall as Borges’ list. These categorizations obey some general principles, not quite the same as modern biologists follow, but not irrational either. Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science is good popular review of ethno-biology, the branch of anthropology that studies different cultures’ theories of biology and systems of classification Did you know there are specialized brain areas that handle animal taxonomy? Or try here for a scholarly treatment.

At the highest level is usually a distinction between plants and animals. This doesn’t necessarily match the biologists’ distinction between Plantae and Animalia, but rather usually follows a distinction between things that don’t and do move under their own power. Even babies seem to make a big distinction between shapes on a screen that get passively knocked around, and shapes that move on their own. i.e. are animated.

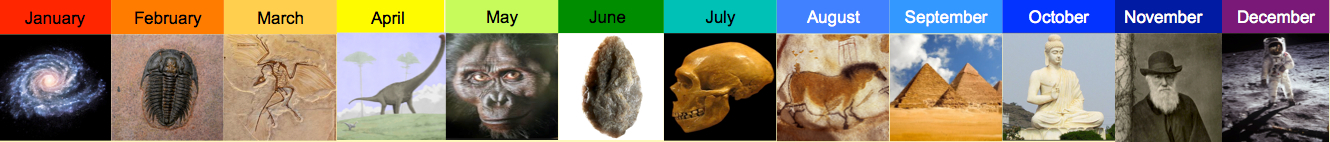

Among larger animals (non-bugs/worms) the first large scale groups to receive a label of their own are almost always birds, fish, and snakes, in no particular order. These categories are telling: each represents a variety of locomotion (flying, swimming, slithering) other than the stereotypical mammalian walking/running. (Many folk classifications lump bats with birds and whales with fish, and they may also separate flightless birds like the cassowary from others.) So whether a creature moves on its own, and how it moves are central to folk categorizations of living kinds, even if not to modern scientific taxonomy. And so finding an animal that seems to be a missing link between two (psychologically) major domains of life — birds and terrestrial animals — is going to be a Big Deal, cognitively, upsetting people’s intuitive notions that it takes God’s miraculous intervention to create animals that fly, or to condemn the Serpent to slither.