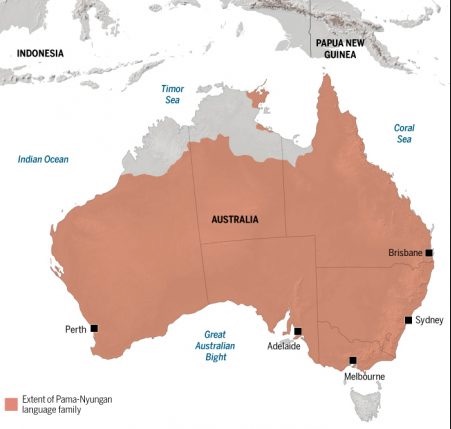

I’m an anthropologist, and I like inflicting kinship on people. Last post was Australian language history; here’s Australian kinship.

Claude Lévi-Strauss thought that the complexities of kinship systems reflect not just adaptation to the physical environment, but also the operation of “fundamental structures of the mind.” (I would agree.) This applies particularly to Australian Aborigines. Lévi-Strauss called them “intellectual aristocrats” of the primitive world, having in mind their complex symbolic life and social organization. Australian Aboriginal systems of kinship and marriage are famously recondite. Generations of anthropology teachers have dragged students through these systems, as earlier generations of Latin teachers dragged their pupils through “amo, amas, amat.” Working out all the details can indeed be tricky. The natives themselves have been known to sketch diagrams, and argue about the correct answers.

Here are two general principles that help understand what’s going on. Both principles are found widely, but not universally, in Australia. Outside Australia, the first principle is widespread (but not familiar to most Westerners), the second is rare (but found a few other places, like western Amazonia, an independent reinvention).

1) Most Aborigines, when they label their kin, and divide them into marriageable and non-marriageable, follow a version of so-called Dravidian rules. (As the name suggests, these are common in southern India, but this isn’t strong evidence for an Australia-India historical connection, because Dravidian rules are found all over the place.) According to the rules, Father’s Brother = Father (i.e. Father’s Brother is called by the same term as Father), but Mother’s Brother gets a different term, which we could translate “uncle”. Mother’s Sister = Mother (i.e. Mother’s Sister is called by the same term as Mother), but Father’s Sister gets a different term, which we could translate “aunt”. With perfect consistency, these equations are carried over to their children. Father’s Brother’s Child = Father’s Child = Sibling, and Mother’s Sister’s Child = Mother’s Child = Sibling. (There may be further distinctions, like breaking down Sibling into Brother and Sister, but I ignore these here.) On the other hand, Mother’s Brother’s Child and Father’s Sister’s Child are not equated with siblings. Very commonly, these principles are used to determine who can marry whom. Parallel cousins (those classified as Sibling, related through parents who are same-sex siblings) are covered by the incest taboo, and off limits for marriage. Cross cousins (those not classified as Sibling, related through parents who are opposite-sex siblings) aren’t covered by the taboo, and may be preferred spouses.

(The Yanomamö of the Orinoco basin are one of many groups that follow – and sometimes break – these rules. Generations of students learned about them from one or another edition of this classic study, by Napoleon Chagnon, who died last year.)

2) Aborigines do something unusual with Dravidian rules in the children’s generation. For us, the important distinction in the Child category is the sex of the child: is he or she female (daughter) or male (son)? But for Aborigines, the important distinction is the sex of the child’s parent: fathers and mothers generally classify their children differently, with one or more terms covering Man’s Child and one or more different terms covering Woman’s Child. So a woman and her husband use different kin terms for their kids. We could call these kin types “fatherling” (the children to whom one is father = Man’s Child) and “motherling” (the children to whom is mother = Woman’s Child.) These terms are commonly extended to other kin. Ask a man who his fatherlings are and he will name his own children, then his brothers’ children (after all, they call him father). Ask a woman who her motherlings are and she will label her own children, then her sisters’ children (after all, they call her mother). But … this is the tricky bit … Ask a man who his motherlings are, and he will name his sister’s children (the children to whom he is Mother’s Brother). Ask a woman who her fatherlings are, and she will name her brother’s children (the children to whom she is Father’s Sister).

This means that the classification of kin in the children’s generation is a mirror image of classification in the parents’ generation. And at some point some clever Aborigine noticed that under this system all relatives fall into just four super-classes – anthropologists call them sections – and everyone can agree on where to draw the boundaries between them. (This is not the case in more standard Dravidian systems, which, like most Western systems, don’t distinguish Man’s Child from Woman’s Child.) So you can go ahead and assign names to these sections, give them totemic animals, and so on. For any individual there will be

a) his or her own section (which also includes Siblings, and some grandkin: Fathers’ Fathers, Mothers’ Mothers, Fatherlings’ Fatherlings, and Motherlings’ Motherlings),

b) a section for his/her Fathers (and Fathers’ Sisters, and Fatherlings), a

c) a section for his/her Mothers (and Mothers’ Brothers, and Motherlings), and

d) a section for his/her potential Spouses (and Siblings-in-law, and some grandkin: Fathers’ Mothers, Mothers’ Fathers, Fatherlings’ Motherlings, and Motherlings’ Fatherlings)

There’s a lot of variation on basic themes across Australia (e.g. systems where sections are further subdivided, yielding eight subsections). It’s likely (but not certain) the kinship terms came first, and the division into recognized sections came later. Not everybody does sections. And some groups have adopted the section system even thought they don’t have the corresponding terms.

If you just skimmed through the part above (that’s OK, it’s not on the exam) here’s an analogy. We (at least most readers of this blog) aren’t used to sorting out kin the way Aborigines do, but we’re used to the idea of voting for candidates supported by different political parties. And we’re also used to the idea that different voting rules have different consequences: a first-past-the-post rule favors a two party system; proportional representation favors many parties. This is the stuff of politics in democratic societies, but imagine how confusing it would be to anyone not used to voting at all . By the same token, odd quirks in the way people categorize kin can have important consequences. Human beings, even in technologically simple societies, don’t just adapt to their natural environment, but also navigate a universe of social rules – what Aborigines call “the Law”.

If you want even more, the AustKin database and websites provides access to kinship terminologies and social category systems from published and archival sources for over 607 Australian Aboriginal languages.