Contact between the Old World and the New was a disaster for the latter. Conquest, mass killing, and enslavement were part of the story, but even more important was the introduction of a whole slew of epidemic diseases – measles, tetanus, typhus, typhoid, diphtheria, influenza, pneumonia, whooping cough, dysentery, and smallpox. In the century and a half after Columbus, the Americas probably lost more than 90% of their native population

The flow of diseases wasn’t entirely one way. In Europe, syphilis is first recorded in Naples, in 1495. It almost certainly came from the Americas, brought back with Columbus’s crew. Columbus himself may have been an early victim. In the Americas, syphilis may have been spread largely through skin contact, but the Old World version was mostly sexually transmitted. The disease initially showed itself in spectacular, gruesome boils and skin lesions, and killed quickly, but eventually evolved to a more slowly progressing version that left victims alive for decades while gradually destroying their circulatory and nervous systems, often ending in insanity.

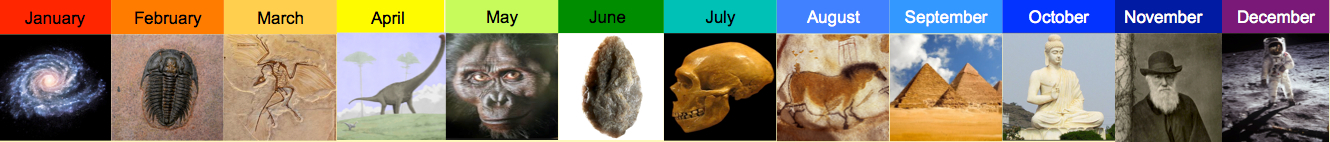

Above: Names for syphilis

Deborah Hayden’s book Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis is a popular overview of the subject. Part of the book is given over to identifying likely cases in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Of course retrospective diagnosis is difficult, a matter of probabilities, not certainties, but Hayden argues that there is good evidence for syphilis for each of the following:

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Franz Schubert

- Jane Austen*

- Robert Schumann

- Charles Baudelaire

- Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln

- Gustave Flaubert

- Guy de Maupassant

- Vincent van Gogh

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Oscar Wilde

- Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen)

- James Joyce

- Adolf Hitler **

Was syphilis as important for European art and literature as drugs were for rock music?

* Just kidding. Sorry.

** Hitler reportedly tested negative for syphilis on the Wassermann test, but Hayden notes that the test isn’t very reliable for the later stages of the disease.