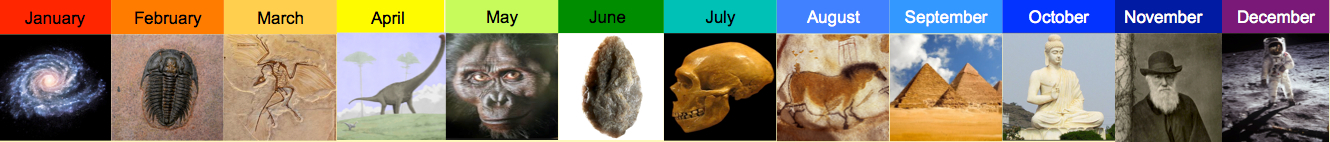

5.31 – 5.03 million years ago

There’s a book from back in 1954, now out of print, called Engineer’s Dreams by Willy Ley (who was most notable as a spaceflight advocate). The book lays out various grandiose engineering projects that people have proposed over the years. Some of these dreams have actually been realized: after centuries of people talking about it, there is now a tunnel under the English Channel.

Others … well …

One project the book discusses is damming the Congo River, creating a huge lake in the Congo basin, then sending the water north to create another huge lake in Chad. (There’s a small lake there now, almost dried out, which was a lot bigger 10,000 years ago when the Sahara was wetter.) From Lake Chad, the water would be sent further north to create a great river – a second Nile — running through Libya into the Mediterranean. All that fresh water is just running uselessly into the Atlantic now. Why not send it someplace where it’s needed?

Another engineer’s dream is to refurbish the Mediterranean Sea by building a dam across the Strait of Gibraltar. This actually isn’t an impossible project. The strait is less than nine miles across at its narrowest, and about 3000 feet deep (about 900 meters) at its deepest. A dam across the strait would have some dramatic consequences. The Mediterranean loses more water from evaporation than it gains from the rivers running into it. The difference is made up by a flow of water from the Atlantic. Cut this off, and the sea will start shrinking. You could let the Mediterranean drop 330 feet (about 100 meters) before stabilizing it, run a huge hydroelectric plant at Gibraltar, and open up a whole lot of prime Mediterranean real estate.

Sadly, whenever people have dreamed great dreams, there have always been small-minded carpers and critics to raise objections. Okay, so maybe the mayors of every port on the Mediterranean would complain about their cities becoming landlocked. And maybe massively lowering the sea level in an earthquake-prone region would lead to a certain amount of tectonic readjustment before things settled down.

So probably the Gibraltar dam will never be built (although Spain and Morocco are considering a tunnel). But we’ve seen already that Mother Nature sometimes plays rough with her children, and it turns out (although Ley couldn’t have known this back in the 50s) that damming the Mediterranean has already been done. The story begins back in the Mesozoic (late March), when the Tethys Sea ran between the northern continent of Laurasia and the southern continent of Gondwanaland. The sea was still around 50 million years ago (April 11) when whales were learning to swim. But it has been gradually disappearing over time. When India crashed into Asia and raised the Himalayas, the eastern part of the sea closed off. And as Africa-Arabia moved north toward Eurasia, a whole chain of mountains was raised up, running from the Caucasus to the Balkans to the Alps. The Tethys Sea was scrunched between these: what’s left of it forms the Caspian, Black, and Mediterranean seas.

Starting about 6 million years ago, the story takes a really dramatic turn. The continents were in roughly there present positions, but the northern movement of the African tectonic plate, plus a decline in sea levels due to growing ice caps, shut off the Strait of Gibraltar, sporadically at first. With water from the Atlantic cut off, the Mediterranean began drying out. By 5.6 million years ago, it had dried out almost completely – the Messinian Salinity Crisis. (The Messinian Age is the last part of the Miocene Period). There were just some hyper-saline lakes, similar to the Great Salt Lake in Utah or the Dead Sea in the Near East, at the bottom of an immense desert more than a mile below today’s sea level. The Nile and the Rhone cut deep channels, far below their current levels, to reach these lakes. This lasted until 5.3 million years ago, when the strait reopened and a dramatic flood from the Atlantic restored the Mediterranean.

All this was happening just around that time that hominins were committing to bipedalism. Did the cataclysmic events in the Mediterranean basin have some influence on hominin evolution in Africa? At this point we can’t say.

Harry Turtledove, prolific writer of alternative history, has a novella, Down in the Bottomlands, set on an alternative Earth in which the Mediterranean closed off, dried out, and never reflooded. In the novella, terrorists are plotting to use a nuclear weapon to reopen the Mediterranean desert to the Atlantic – sort of Engineer’s Dreams in reverse.

And here’s a completely unrelated post about bottoms.