Continuing yesterday’s post: What accounts for the differences between classical Greek and early Chinese intellectual traditions? Below are a few things that might be involved; this is hardly a complete list.

Non-degenerate limit random variables

Here’s a nice little puzzle involving probability:

Take a bag with two marbles in it, one red and one green. Draw a marble at random. Put it back in the bag, and add another marble of the same color. Repeat: randomly draw one of the (now three) marbles in the bag, put it back, and again add a marble of the same color. Continue, adding a marble every time. What happens to the frequency of red marbles as the number of marbles in the bag goes to infinity?

Answer: When you carry out this procedure, the frequency approaches a limit. As the number of marbles grows larger, you sooner or later get, and stay, arbitrarily close to the limit. Now carry out the same infinite procedure a second time. This time you also approach a limit. But the limit this time is different! The first time, the limiting frequency might be .23748… . The second time it might be .93334… . If you keep on doing the infinite experiment a bunch of times, you’ll approach a different limit every time, with the various limits uniformly distributed over the interval [0,1]. These are non-degenerate limits. This is different from what you get when you flip a fair coin infinitely many times. The frequency of heads will always approach the same “degenerate” limit, .50000… .

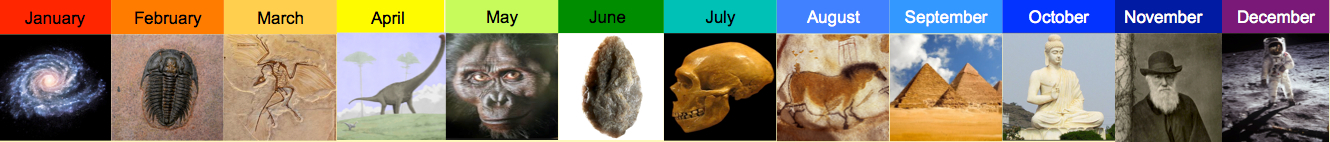

A chance element like this is probably involved in the intellectual traditions of major civilizations. The first few great thinkers to come along have a massive influence on the direction of intellectual life, just as picking a red or green ball on the first round makes a big difference to the final limit. So Pythagoras’ and Plato’s obsessions with numbers and geometry as the keys to the universe have a disproportionate influence on later Western thought (allowing that the “Pythagoras” we know is encrusted with legends). Subsequent thinkers have progressively less and less influence, just as picking a green or red ball when there are already a hundred balls in the bag doesn’t make much difference in the ultimate limiting frequency.

Temperament

But there may be more systematic things going on. Daniel Freedman was a psychologist, white, married to a Chinese-American woman. While awaiting the birth of their first child, the couple found that relatives on the two sides of the family had very different ideas about how newborns behave. Freedman was sufficiently intrigued that he carried out an investigation of assorted newborns in a San Francisco hospital, including babies of Chinese and European origin.

It was almost immediately apparent that Chinese and Caucasian babies were indeed like two different breeds. Caucasian babies started to cry more easily, and once started they were more difficult to console. Chinese babies adapted to almost any position in which they were placed.. … In a similar maneuver … we briefly pressed the baby’s nose with a cloth, forcing him to breathe with his mouth. Most Caucasian and black babies fight this … by immediately turning away or swiping at the cloth. However … the average Chinese baby in our study … simply lay on his back, breathing from his mouth. … Chinese babies were … more amenable and adaptable to the machinations of the examiners. p. 146

This might seem like a minor curiosity, but it fits neatly with later work demonstrating East-West differences in adult cognitive styles. This raises the possibility that differences in temperament evident at a very early age might influence the evolution of intellectual traditions.

Coinage

Coined money apparently initially appeared in Lydia, in Asia Minor, around 600 BCE. It was quickly taken up by the Lydians’ Ionian Greek neighbors. And it is in Ionia too that we find the earliest philosophers. In Money and the Early Greek Mind, Richard Seaford argues that these developments are connected. The monetization of the Greek economy accustomed Greeks to the idea that a common impersonal material measure of value, relatively independent of individual control, underlay the multifarious goods and services produced by the polis economy. This led in turn to the pre-Socratic philosophers, who were obsessed with finding the one impersonal natural element – water, air, number – of which the whole heterogeneous variety of the natural world was made.

In Athens, the expansion of a monetary economy led to a curious insult – opsophagos, or fish-eater. What made this an insult is that fish were sold in the marketplace. They were a mere commodity, free of the ritual and taboos that surrounded the sacrifice and distribution of animal flesh. The fish-eater was a rich man indulging the pleasures of consumption free from the constraints of tradition and decorum. And his conspicuous consumption offended not only tradition but the spirit of democracy. Better that he spend his wealth on the public good.

In traditional China, by contrast, coins, and later paper money, would challenge but never break the hold of state patriarchy. And Spartans too recognized the subversive potential of money. Sparta used iron bars for money, precisely because they were inconvenient.