Linnaeus chose one trait – mammary glands / lactation – to define the order Mammalia. This was not a purely scientific decision. Like many authorities in eighteenth century Europe, he was concerned that the common practice of wet-nursing was unnatural and dangerous, and he wrote a pamphlet urging the advantages of women nursing their own infants.

But mammals do not owe their Cenozoic success to any one trait. True, there is a central theme in mammalian evolution.

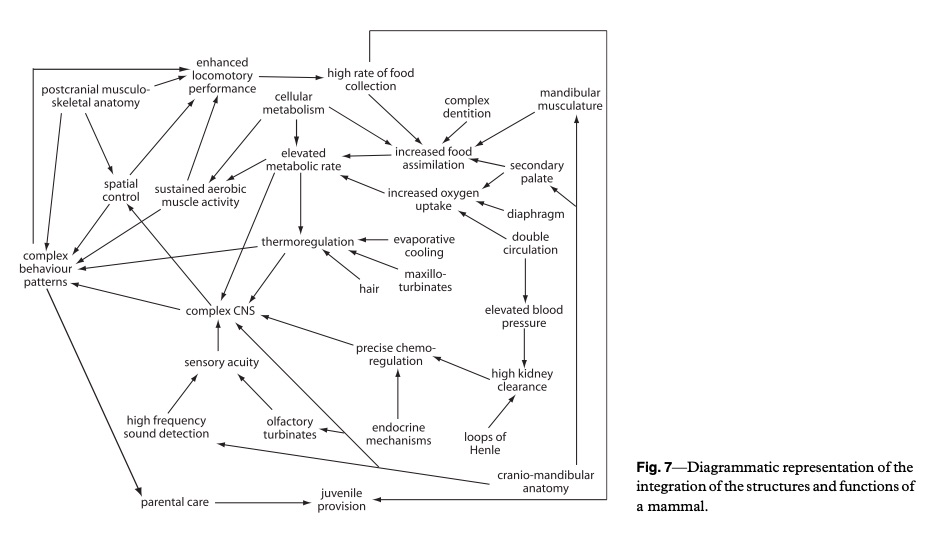

[T]he over-arching attribute manifested by the origin of the mammals is increasing homeostatic ability: the maintenance of a constant internal environment in the face of a fluctuating external environment, by means of high-energy regulatory processes (Kemp p. 18)

But this homeostatic ability is supported by a whole series of interrelated traits that evolved in tandem. Here’s a summary diagram.

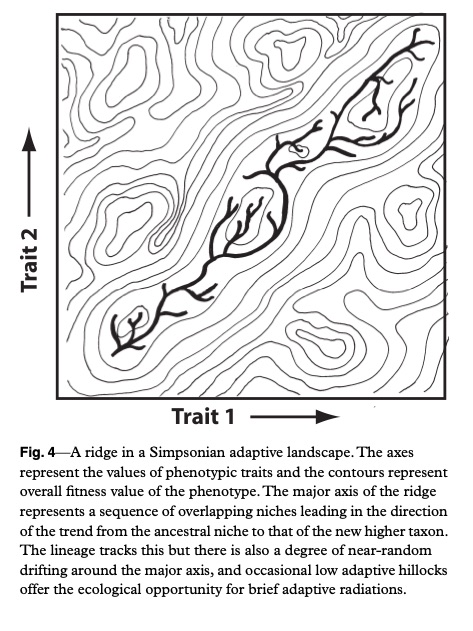

Evolving a whole set of coordinated traits like this is a much slower business than optimizing a single trait. It is a matter of correlated evolution, in which small changes in one character allow for small changes in other characters, along an “adaptive ridge.”

It took several hundred million years, from synapsids, to therapsids, to cynodonts, to mammals, to put the mammalian package together. And even after mammals had appeared and begun to diversify, it would take an extraordinary catastrophe at the end of the Cretaceous before the Age of Mammals would really begin.

For an excellent popular introduction, try I Mammal: The Story of What Makes Us Mammals