Homer’s Iliad records 240 battlefield deaths, 188 Trojans and 52 Achaeans.

Those who had dreamed that force, thanks to progress, belonged only to the past, have been able to see in the Iliad a historical document; those who know how to see force, today as yesterday, at the center of all human history, can find there the most beautiful, the purest of mirrors.

Simone Weil, “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force,” 1940-1941

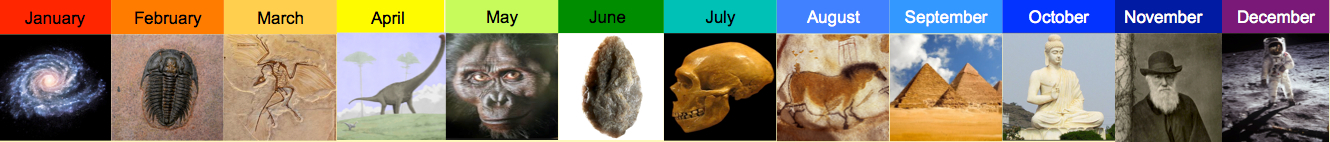

Some things we know (probably) about Late Bronze Age Trojans and Greeks.

- Troy is represented by the archeological site of Hisarlik, in Turkey near the Dardanelles. It covered over fifty acres and probably had a population in the high thousands. The kingdom of Troy was a client state of the Hittites, known to them as Wilusa (Greek Ilion).

- Troy was devastated after 1300 BCE, maybe by an earthquake, and again, just after 1200 BCE, by fire. There are earlier episodes of destruction as well.

- The Hittites knew a kingdom to their west called Ahhiyawa. The Ahhiyawans were probably the people known to Homer as the “Achaeans,” i.e. the Greeks. The Egyptians knew a kingdom to their north, beyond Kefta (= Crete = Biblical Kaphthor), called Danaja, whose chief cities match those of Mycenaean Greece. The Danajans probably correspond to the “Danaans,” an alternative Homeric name for the Achaeans. Ahhiyawa/Danaja may have been a single state, with vassal kings under the rule of a “King of Kings,” capitol Mycenae.

- Homer probably composed the Iliad in the eighth century BCE (762 BCE, give or take 50 years, according to recent research applying evolutionary models to the text), or the seventh century (according to Martin West, who also thinks the Iliad and the Odyssey had different authors). But Homer relied on sources – presumably earlier oral poems – that went back centuries earlier. The names he gives for the Greeks were not current in his own time. Many lines of his epics only scan if he was drawing on poetic formulas from a Bronze Age dialect of Greek. The cities he lists among those who contributed to the war effort match the Bronze Age better than his own time. And he is familiar with Bronze Age helmets and shields that had long since gone out of use.

So the story of the Trojan war dates back to the Bronze Age, and incorporates real geography and material culture. Just how true the story itself is less certain. It has had an enormous influence of course. Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that England’s first king was a descendant of refugees from fallen Troy. Sultan Mehmet II claimed to be avenging the Trojans when he conquered Constantinople in 1453.

In addition to the more standard translations of the Iliad – Richmond Lattimore’s is the most faithful, and still probably the best – there is also a recent adaptation ( not really a translation) by “The War Nerd.” The War Nerd is a persona created by “Gary Brecher,” the pseudonym of sometime poet John Dolan, who has been turning a sharp, misanthropic, Irish eye on wars past and present for years.

There a many books on the Trojan War (apart from the ones by Homer). Here are some good ones.

- Barry Strauss The Trojan War: A New History The factual basis of the story, based on recent research.

- Adam Nicholson Why Homer Matters The Iliad as a clash between the descendants of steppe warriors and the urban culture of the Mediterranean

- Jonathan Gottschall The Rape of Troy: Evolution, Violence, and the World of Homer Literary criticism meets evolutionary psychology. Great stuff, although it turned out not to be a great career move in today’s academic environment. Gottschall went on to write a book about his adventures as a cage fighter, The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch.

And a remark on war in the lives of ants and men.

Pingback: Consider her ways | Logarithmic History

Pingback: Consider her ways | Logarithmic History