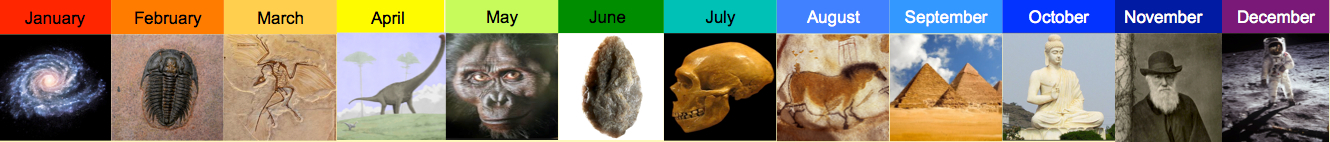

99.9 – 95.6 million years ago.

Here is my obituary for Ed Wilson (1929 – 2021) and below some thoughts about ants.

There are some pieces of paleontology that really stand out in the popular imagination. Dinosaurs are so cool that even if they hadn’t existed we would have invented them. (Maybe we did, in the form of dragons. And look ahead (or back) to early April for the dinosaur-griffin connection.) Also, as I suggested in a previous post, transitions from one form of locomotion to another – flightless dinosaurs to birds, fish to tetrapods, land mammals to whales – really grab the imagination (and annoy creationists) because the largest and most distinctive named folk categories of animals (snakes, fish, birds) are built around modes of locomotion.

Evolutionary biologists tend to see things differently. Turning fins into legs, legs into wings, and legs back into flippers is pretty impressive. But the really major evolutionary transitions involve the evolution of whole new levels of organization: the origin of the eukaryotic cell, for example, and the origin of multicellular life. From this perspective, the really huge change in the Mesozoic – sometimes called the Age of Dinosaurs – is the origin of eusociality among insects like ants and bees. An ant nest or a bee hive is something like a single superorganism, with most of its members sterile workers striving – even committing suicide — for the colony’s reproduction, not their own. (100 million years ago – corresponding to March 28 in Logarithmic History — is when we find the first bee and ant fossils, but the transition must have been underway before that time.)

Certainly the statistics on social insects today are impressive.

The twenty thousand known species of eusocial insects, mostly ants, bees, wasps and termites, account for only 2 percent of the approximately one million known species of insects. Yet this tiny minority of species dominate the rest of the insects in their numbers, their weight, and their impact on the environment. As humans are to vertebrate animals, the eusocial insects are to the far vaster world of invertebrate animals. … In one Amazon site, two German researchers … found that ants and termites together compose almost two-thirds of the weight of all the insects. Eusocial bees and wasps added another tenth. Ants alone weighed four times more than all the terrestrial vertebrates – that is, mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians combined. E. O. Wilson pp 110-113

E. O. Wilson, world’s foremost authority on ants, and one of the founders of sociobiology, thinks that the origin of insect eusociality might have lessons for another major evolutionary transition, the origin of humans (and of human language, technology, culture, and complex social organization). In his book The Social Conquest of Earth he argues that a key step in both sets of transitions was the development of a valuable and defensible home – in the case of humans, a hearth site. Wilson returns to this argument in his recent book Genesis: The Deep Origin of Human Societies. On the same topic, Mark Moffett’s book The Human Swarm: How Human Societies Arise, Thrive, and Fall, asks how it is that we somehow rival the social insects in our scale of organization.

One trait found in both ants and humans is large-scale warfare. Wilson gives an idea of the nature of ant warfare in fictional form in his novel Anthill. It’s an interesting experiment, but also disorienting. Because individual recognition is not important for ants, his story of the destruction of an ant colony reads like the Iliad with all the personal names taken out. But Homer’s heroes fought for “aphthiton kleos,” undying fame (and got some measure of it in Homer’s poem). The moral economy of reputation puts human cooperation in war and peace on a very different footing from insect eusociality. (Here’s my take on “ethnic group selection,” which depends on social enforcement, perhaps via reputation.)

“Consider her ways” is the title of a short story by John Wyndham, about a woman from the present trapped in a future ant-like all-female dystopia. It was made into an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The title is from Proverbs 6:6, “Go to the ant, thou sluggard, consider her ways and be wise.”

Other science fiction authors have taken a cheerier view of a world without men.

Pingback: Slime had they for mortar | Logarithmic History