Reuben, Reuben, I’ve been thinking

What a fine world this would be

If the men were all transported

Far beyond the northern sea.

Oh, my goodness, gracious, Rachel,

What a strange world this would be

If the men were all transported

Far beyond the northern sea.

Reuben, Reuben, I’ve been thinking

What a great life girls would lead

If they had no men about them

None to tease them, none to heed.

Rachel, Rachel, I’ve been thinking

Life would be so easy then

What a lovely world this would be

If you’d leave it to the men.

Reuben, Reuben, stop your teasing

If you’ve any love for me

I was only just a-fooling

As I thought, of course, you’d see.

Rachel, if you’ll not transport us

I will take you for my wife

And I’ll split with you my money

Every pay day of my life!

(Traditional song, many versions)

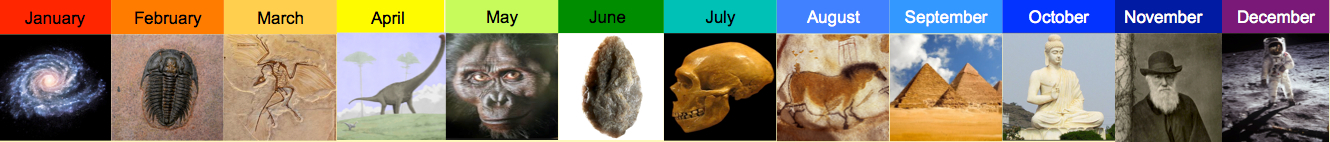

I once heard William Hamilton, the evolutionary theorist, give a talk where he suggested, among other things, that human beings might give up sexual reproduction in the future. He was building on a familiar evolutionary puzzle: sex, or more exactly the division between female (large, expensive gametes) and male (small, cheap, mobile/motile gametes) is a very expensive proposition. Imagine a sexually reproducing population in which females average two offspring each, one female, one male. On average, each female is replacing herself in the next generation with one daughter. Now imagine a mutant asexual female. She also gives birth to two offspring, but the offspring are both daughters, clones of their mother. The numbers of this mutant lineage will initially double in every generation, and they will eventually replace the sexually reproducing type entirely.

Unless … There must be some advantage to sexual reproduction to make up for this huge disadvantage. One possibility is that sex somehow makes it easier to avoid the accumulation of deleterious mutations. Another possibility, which Hamilton was pushing, is that sex gives an advantage to host species in their evolutionary arms races with parasites. A species consisting of lots of genetically uniform clones is more vulnerable to pathogens.

However … (and this is where Hamilton was going) a species that has developed medical technology to the point that it no longer has to worry so much about infectious disease might be able to dispense with sexual reproduction. So Hamilton pondered a germ-free hygienic future in which the clonal offspring of one or more fit, fecund, philoprogenitive females replaced the rest of the human race.

And … minus the evolutionary theorizing, some science fiction writers have imagined futures without a division between men and women. John Wyndham, writing back in the 1950s imagined a world in which a plague had wiped out men, and the surviving women carried on high tech reproduction without men in an ant-like caste society. Wyndham thought this was a bad thing, but for some feminist science fiction writers in the 1970s – Joanna Russ, James Tiptree, Jr. – a world without men was imagined as a utopia.

The most sustained piece of world-building of a society without “men” and “women” comes from Ursula Le Guin. The aliens on the planet Winter are much like humans on Earth, but they are hermaphrodites. Most of the time they are neuter, with underdeveloped male and female organs. But during kemmer (estrus, the breeding season), two individuals will pair off and develop complementary sexual characters and sexual desires. One member of the pair will temporarily develop as a female, the other as a male. They will copulate much as we do, and the female member of the pair will conceive and eventually give birth. The next time kemmer rolls around, the former female may develop as a male, and her former (and formerly male) partner (or another) may develop as a female.

Le Guin, the daughter of two anthropologists, gives us a richly developed thick description of the culture of Winter, not a utopia, but just another world, different from our own in some ways, similar in others. But what’s missing from her story is much consideration of the evolutionary dynamics underlying the exotic (to us) reproductive biology. In Le Guin’s scheme, the female member of a pair is still putting more energy than the male into producing a child. We have to expect that there will be considerable jockeying, both physiological and psychological, over who, in each reproductive episode, takes on the more burdensome role. On Winter, the Battle of the Sexes will still be fought, albeit on different terrain.

Meanwhile, back on Earth, Reuben, Reuben is a comic novel about the Battle of the Sexes in 1950s suburban Connecticut. The novel centers on the priapic poet Gowan MacGland, (obviously modeled on Dylan Thomas), who takes advantage of an American tour to enjoy the opportunities available to an alpha small-gamete-producer. Up to a point, anyway: the terrible lesson he learns is never, ever, ever cuckold your dentist.

Pingback: Consider her ways | Logarithmic History