Our descent, then, is the origin of our evil passions!! The devil under form of Baboon is our grandfather.

Charles Darwin, Noteboook M

Maimoun angushti shaitan ast.

(A monkey is the devil’s fingers.)

Tajik proverb

Monkeys and apes are not only exceptionally brainy, but also distinctively social. Most mammals are solitary (apart from mothers and their juvenile offspring of course). Among a minority of mammals, adult males and females set up pairbonds. And some mammals form larger groups. In most cases, however, these are relatively unstructured aggregations: a herd of buffalo is more like a crowd of people than a human community. A handful of mammals – elephants, cetaceans, and the majority of monkeys and apes – form more structured groups, enduring and internally differentiated.

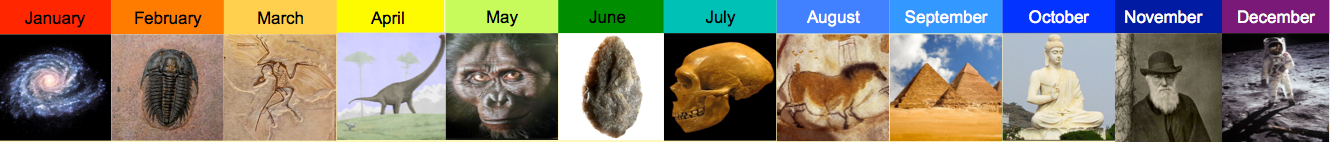

Social evolution is path dependent: primate social organization is affected by ecology, but also has a strong phylogenetic component. This makes it possible to offer a tentative reconstruction of the stepwise evolution of stable sociality in primates. Here’s an evolutionary tree, showing inferred transitions between solitary living, and multimale/multifemale, unimale/multifemale, and pairbonded groups:

A diagram of the possible evolutionary dynamics looks like this:

And the accompanying story goes like this: about 52 million years ago, the solitary nocturnal ancestor of monkeys and apes switched to being diurnal. This allowed for the exploitation of a whole range of new foods, but it also exposed the ancestor to new forms of predation. The first step in the evolution of monkey and ape sociality, then, was aggregation in multimale/multifemale groups to cut predation risk. At first these groups would have been loosely structured and unstable, but eventually they would have evolved into something like what we see today among most Old World monkeys: stable (sometimes lifelong) networks of relatives and friends, dominants and subordinates, nested within enduring communities.

A later development, going back to 20 million years ago or less, was a shift, among some of these social primates, to unimale/multifemale groups, or pair-living family groups.

The inferred development of structured social groups in primates bears a remote similarity to the evolution of eusociality among social insects. According to current theories, the starting point for eusociality is the development of a defended nest site where females lay eggs and raise offspring. Sometimes an established nest site is so valuable that it’s adaptive for the next generation of offspring to stay on when they mature rather trying to found new nests. The eventual result may be the evolution of a highly structured society, with strong reproductive skew: some nest members specialize in reproduction, others in foraging or defending the nest. The latter may evolve into an obligately sterile caste.

Primates too have developed an intensified, structured sociality as a response to obligate group living. But the parallels with eusocial insects go only so far. The great majority of primates give birth to one offspring at a time. There are no queen bee baboons whelping one vast litter after another and pushing subaltern kin into caring for them. This goes for humans as well. Our species matches the social insects in the scale of cooperation, but we manage this through a complicated dance of coalition-building and reputation management. For a primate, building a honey-bee style superorganism has to be an aspiration rather than a reality.

Pingback: Oak ape | Logarithmic History